Armed teachers aim to defend K-12 schools

“Stop. Drop your weapon. Don’t shoot.”

Kasey Hansen yelled as she pointed her loaded handgun at a target’s chest at a shooting range outside Salt Lake City.

“I want to protect my students,” said Hansen, a special needs teacher in Utah. “I’m going to stand in front of a bullet for any student that is in my protection and so I want another option to defend us.”

Hansen carries her pink handgun, Lucy, with her every day to each of the 14 schools in which she teaches. The 26-year-old teacher works with elementary, middle and high school students with hearing impairments in the Granite School District.

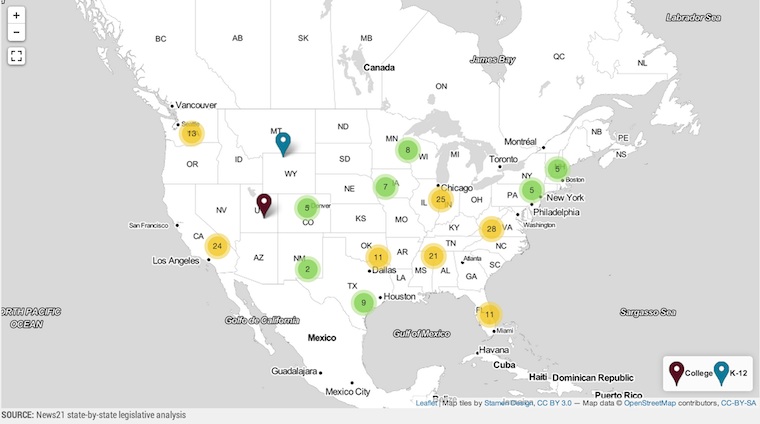

She is one of an unknown number of armed teachers across the country. In 28 states, adults who legally own guns will be allowed to carry them in public schools this fall, from kindergarten classrooms to high school hallways. Seven of those states specifically cite teachers and other school staff as being allowed to carry guns in their schools.

But a News21 examination of open-records laws in those states found that teachers or staff who choose to carry a firearm into their classrooms are not required to tell principals, other teachers or parents. Only five of those states have completely open access to concealed carry permit information through public records requests. Some state’s laws completely seal off those records and others are silent on the issue.

In states where it is legal, parents may have no idea that their child’s teacher carries a gun into the classroom every day.

School administrations can decide to gather the information, but they don’t have to disclose to anyone. From the office of the superintendent to a secretary’s desk, there is no file that contains the information.

After the December 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, the threat of an attack by an armed gunman in elementary and high schools prompted five states to give school administrators the authority to arm their teachers. In 2013, legislation was introduced in at least 33 states related to arming teachers or school staff, but of the more than 80 bills introduced, only Alabama, Kansas, South Dakota, Tennessee and Texas enacted laws related to public schools, according to a report by the Council of State Governments.

Connecticut law, which previously let school officials allow people other than police to carry in schools, was revised after Newtown, so that only officers can carry guns on school grounds. Georgia passed a guns-in-schools bill this year. The other 22 of the 28 states allowing guns in schools already had versions of such laws in place.

Teacher Kasey Hansen poses with her gun inside one of her classrooms at Valley Junior High School on June 12, 2014. Photo by Jacob Byk/News21.

In some cases, school districts and local school boards can designate school faculty to get specific training in order to carry. A few states, including Hawaii and New Hampshire, don’t set policy in state law. In Utah and Rhode Island, anyone with a concealed carry weapons permit can bring a firearm onto public school grounds.

Schools in some states, including Colorado and Arkansas, are getting around the law by employing teachers, administrators and other staff members as security officers, so that they can be armed in the school. And most states allow guns in schools for approved programs and events sanctioned by the school.

Utah gun culture fosters armed teachers

In Utah, guns are commonplace in public, with more than a half-million people holding a concealed firearm carry permit. Residents with a permit can legally carry almost anywhere in public, from elementary schools to local restaurants and bars to municipal parks. Families pack rifles alongside sleeping bags in their camping gear, shooting ranges are popular date spots and Duck Hunt is more than just a video game.

The Utah law that allows anyone with a concealed carry permit, including teachers, to carry on school property has been in place for more than a decade. A provision that would have restricted possession on school property was taken out of the bill when it passed.

Hansen got her concealed carry permit a week or two after Sandy Hook and participated in a free training course offered to teachers. She then bought her pink-plated Cobra 380 handgun, and started carrying it in her classrooms about seven months ago.

“I never really thought about it before Sandy Hook,” said Hansen, who was teaching when she heard about the attack. “It just killed me. It’s something personal when you mess with students or children, teachers take it very personally and it’s as if you were messing with one of our own.”

Hansen has been a teacher for four years. She found her calling while taking an introduction to special education class at Brigham Young University - Idaho.

“We had to go out into the community and volunteer with special-needs people,” Hansen said. “It was just that that made me fall in love with the special-ed kids, and I knew that’s where I was meant to be.”

Hansen grew up in Salt Lake City, in a state with some of the loosest gun laws in the nation, but wasn’t raised in a gun-toting family. Teaching at multiple schools a day, Hansen drives around the school district in her white Mazda personalized with eyelashes on the headlights. She works one-on-one with each of her students on language skills, vocabulary, and reading comprehension among other subjects. All of Hansen’s students have hearing aids or a cochlear implant, which could make an emergency situation particularly chaotic.

“It just kind of hit home that I’m a teacher and I’m responsible for the students for x amount of hours a day so I have to protect them,” Hansen said. “I wouldn’t ever leave my kids. I would 100 percent protect them.”

Handling a gun and having the composure to fire it in the event of a shooter entering a school isn’t part of the curriculum taught to education majors nor are those responsibilities outlined in a teacher’s handbook.

“I think every teacher should carry,” Hansen said. “We are the first line of defense. Someone is going to call the cops and they are going to be informed, but how long is it going to take for them to get to the school? And in that time, how many students are going to be affected by the gunman roaming the halls?”

“I’m not the best shot, but I can hit a target,” Hansen said. She goes to the shooting range every couple of months to practice.

In the 10 years since teachers have been allowed to carry guns in Utah, no fatal K-12 school shootings have occurred. Some argue that schools aren’t falling victim to attacks because of their unique, additional security measures. Others think guns in classrooms present more risk than potential for reward.

Kasey Hansen is a special education teacher in Salt Lake City who brings a gun to her classrooms every day.

“I don’t deny the fact that a gun could be used to protect students,” Steven H. Gunn said, “but a gun in school is far more likely to lead to the harm of an innocent individual than to the protection of innocent people.”

Gunn, a member of the board of directors of the Gun Violence Prevention Center of Utah, is also a Holladay City Councilman whose office in City Hall used to be in an old school building. Working there and going home every night to a wife who teaches at a local junior high school gives Gunn an authentic sense of angst.

“A teacher could begin returning fire to a person who is attacking the school and in the process, kill children,” Gunn said. “It’s just a very unhealthy, unsafe situation and teachers, unless they receive special training, simply wouldn’t know how to handle a crisis situation.”

Gunn is also concerned with the message it sends. He believes it creates an unnecessary sense of fear for students that they are in danger.

“It creates the impression on the part of the student that he is in an unsafe environment and that it is necessary for people to protect him with firearms in his school,” Gunn said. “They should have the feeling that where they are studying and where they are with other children is a safe environment. And by carrying a gun, a teacher gives the wrong impression that it is not.”

Ten miles north of Holladay, Ted Hallisey stepped out of his forest-green Ford pickup truck at the south end of the Utah State Capitol in Salt Lake City. With a rugged sort of sophistication, the volunteer physical education teacher walked up the stairs, thumbs tucked into the pockets of his blue jeans.

A cowboy head-to-toe in black Ariat boots, a black Stetson hat and a gold plated 1999 Days of 47 Rodeo belt-buckle, Hallisey was a stark contrast to the building’s white marble steps and pillars made of locally mined Utah granite. For Hallisey, it was important to address the school gun rights issue at the most official place where rights are supposed to be honored and discussed.

Holladay City Council member Steven Gunn is a member of the Gun Violence Protection Center of Utah’s board of directors. Behind him, class pictures hang in what was once the principal's office of a school that now serves as city hall. Photo byJacob Byk/News21.

“Everybody is focused on individual rights, ‘It’s my right to carry a firearm,’ but what about everybody else’s right to be in a safe gun-free environment, especially in schools?” Hallisey asked. “How does that work where they say now your rights don’t matter anymore?”

As a teacher and kid’s health advocate, Hallisey believes there is too much risk in arming a teacher or staff member.

“The likelihood of having to pull that weapon in an attack is pretty slim,” Hallisey said. “The opportunity for them to have an accident carrying the weapon is a lot more pronounced and a lot more likely. I don’t want that teacher to have an accident with their firearm while my student is in their class.”

Hallisey was raised in the Western lifestyle in a rural area where guns were part of the family. His cowboy background combined with his educational experience tells him kids are best kept safe by avoiding the people who would do them harm.

“I don’t see arming their teacher with making them feel more safe, it gives them this fear that every day I go to school there could be an attack,” Hallisey said. “We kind of want to put that out of their mind and just have the preparation instead of the reaction.”

Children’s health advocate Ted Hallisey said he opposes guns in schools. He runs the Cowboy Ted's Foundation for Kids, a health organization in Bountiful, Utah. Photo by Jacob Byk/News21.

Just down the street from the Capitol, stay-at-home mom April Jolley reloads Nerf guns for her sons in their eighth-floor apartment overlooking the Mormon temple in the heart of the city. Jolley, whose three young boys will attend Ensign Elementary School in Salt Lake City, said she would feel safe knowing her kid’s teacher had a gun.

“I think, as teachers, you need to realize that your role is not only to teach them, but you really are like a parent to them,” Jolley said, “You’re protecting them from what could be there.”

For Jolley, the fear of who could come in and attack outweighs the fear of a teacher using a gun in a situation where it wasn’t necessary. A teacher having a gun in a classroom makes her feel safer as long as that teacher has training and knows how to properly use it, she said.

“I think it’s better that they gave teachers one, as long as it’s secured in a place that the kids can’t get to it,” Jolley said. “I don’t think it would be a danger. If anything it’d keep them more protected. They could take it out and protect their own students in the class.”

For Jolley, whose oldest son is entering kindergarten in the fall, the fear of a school shooting is just as prevalent as the fear of her kids being kidnapped.

“When they leave for school, I pray every morning that they’re safe because you don’t know what’s going to happen everyday,” Jolley said. “And I am fearful, but it’s not something I try to think about every day, because to me it’s by chance, it’s not something you could prevent one way or the other.”

Jolley said her kids see guns as more of a novelty, and they know that if you see one you don’t touch it because you never know if it’s loaded.

Schools are making efforts to put more stringent security measures in place, including trained law enforcement officers, strict hall access rules with automatic locks on closed doors throughout the school day and additional emergency drills.

The National Parent Teacher Association has been active in the conversation about guns in schools and gun violence prevention. Although the PTA supports citizens’ rights to bear arms, the organization believes that certain restrictions should be made to reduce violence and incidents that involve firearms. In its position statement on gun safety and violence prevention, which was adopted in 1999, the National PTA said the most-effective day-to-day school climate is one that is gun-free.

In 2013, after the tragedy in Newtown and the introduction of legislation across the country, national education organizations responded.

“As a result of the tragedy and proposals, National PTA amended its position statement to add that the association defers to local collaborative decision making to allow for the presence of armed law enforcement only,” Heidi May, the National PTA media relations manager, said in an email. “The preference of the association, however, is for schools to be gun-free.”