Data show suicides using guns double the number of murders

Americans are twice as likely to die from turning guns on themselves as they are to be murdered with one.

A national News21 analysis of 2012 data found 18,602 firearm suicides in 44 states compared with about 9,655 firearm homicides in 49 states. That means at least 50 people died per day from firearm suicide; 26 died from firearm homicides.

Gun shops and ranges in areas with high rates of suicide are teaming up with prevention specialists to prevent firearm suicides. Range employees are learning the warning signs of suicide to stop mentally unstable people from getting their hands on guns.

News21 contacted all 50 states seeking suicide data for 2012, the most recent year available, but Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island denied requests for statistics or could not be reached. The FBI received limited homicide data from Illinois and Alabama and none from Florida.

Of the 44 states with 2012 data, Montana had the highest rate of suicide by gun, while New Jersey had the lowest.

That firearm suicides outnumbered firearm homicides doesn’t surprise Matthew Miller, who studies suicide at the Harvard Injury Control Research Center. Suicide rates have been higher than homicide rates for as long as Miller remembers, but many people still assume they are more likely to die in a mass shooting than they are by shooting themselves, he said.

Living with a gun in the home makes residents more likely to die from suicide, because they’re more likely to attempt suicide using a gun — and with guns, there’s no turning back, Miller said.

The public doesn’t hear about firearm suicides often because of the stigma surrounding suicide and people who kill themselves, he said.

“I think what we see in the media, whether it’s newspapers or television or movies, there have been people shooting at one another with guns, but rarely do you hear information about suicide,” Miller said.

Firearm suicides in the states studied made up 51 percent of the 35,831 total suicides in those states in 2012, News21 found. For the previous five years, firearm suicides made up just under half of all suicides throughout the U.S., according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data.

Suicide by firearm has been loosely studied for the past 20 years by the American Association of Suicidology, a research and education organization based in Washington, D.C., that was created in 1968. But most experts concentrate on the motives of suicide victims and not the means people use. Prevention specialists are increasingly studying the link between guns and suicide.

Death and gun ownership: Is there a connection?

Experts say having a gun in the house greatly increases the chance someone will use that gun on themselves. States with high rates of firearm suicide generally have high gun ownership.

Alan Berman, former director of the American Association of Suicidology, said there is a direct correlation between gun ownership and death by suicide. Studies show having a gun in the home makes firearm suicide more likely, and can be higher based on gender, age and gun storage.

People choose their method of suicide due to its accessibility, Berman said.

Safe-storage laws are among the few measures suicide analysts agree could help lower firearm suicide rates, because they put a buffer between the mental impulse to end one’s life and the firearms available, Berman said.

“The problem of course is the NRA (National Rifle Association) and their interpretation that any attempt even to talk about safe storage is the beginning of gun control,” Berman said.

Legislation isn’t necessary to promote gun safety, said Don Turner, Nevada Firearms Coalition president.

“As a responsible gun owner, we have the obligation to make sure that our

firearms are kept secure and under control, and that we only sell or give firearms

to people who are not at risk,” Turner said. “All the time and energy put into limiting access to firearms could be put into improving our mental health system. It would probably yield better results.”

Nationally, firearm suicide rates haven’t changed much over the past 20 years that Berman has studied them. However, some states with prevention programs have had success in lowering rates, he said.

“There are efforts,” Berman said. “But again, they are small-scale efforts relative to a large-scale national issue, which no one has the key to the lock yet.”

Suicide generally stems from a buildup of depression and internal despair, said Cathy Barber, creator of Means Matter — a Harvard research group that studies access to guns or other means of suicide.

It’s not unusual for suicidal people to make several plans or attempts to kill themselves, but experts are noticing a trend of more impulsive suicides with firearms, she said. A survey showed 47 percent of people who attempted suicide did so within 10 minutes of thinking about it, she said.

“For the person who is going from 0 to 60 in a few seconds, you don’t want that person to have access to something that could really quickly kill them,” Barber said. “You want to try to build some delay in them being able to get their hands on something that could kill them.”

Bill Smallwood trains his employees to look for warning signs so they don't sell guns to people considering suicide. Smallwood knew four people who killed themselves.

Gun owners have higher rates of suicide than non-gun owners, but they don’t have higher rates of attempts, according to a study on which Barber worked. They don’t have higher rates of mental illness and aren’t more likely to kill themselves. They are just more likely to use a more final means for suicide, she said.

Voluntarily relinquishing firearms to a friend or loved one during times of depression, high stress or mental anguish removes the temptation of turning to a gun when someone might be contemplating suicide, Barber said.

Any means necessary

After his son killed himself in 2003, Stephen Johnson, of Las Vegas, installed a gun safe in his garage. Now, Johnson encourages anyone with guns to lock them up for safety.

His 18-year-old son grabbed a Smith & Wesson handgun from a knapsack in his parents’ closet and shot himself in the shower.

Johnson felt guilty about it for a long time. The guilt eventually stopped. The pain never did.

In his suicide note, Levi Johnson said he would’ve killed himself regardless of the means. The note he left behind took fault with his brief time in the Marines and told his Mom not to blame his Dad for the gun, because if the gun hadn’t been available he would have just used a knife or something else.

“Why? You ask that question, oh, a billion times,” Stephen Johnson said. “I still don’t have the answers of why, but I have been able to cope with that — not getting those questions answered.”

It was the second time Johnson’s son tried to kill himself. During basic training, he tried to overdose on aspirin. In high school, he had a history of cutting himself.

Levi Johnson planned his last attempt. He cleaned his room, made his bed and put his last two paychecks and his ATM code on a bulletin board.

Then he picked up the phone and called the police to forewarn them of his suicide. He hung up, turned the phone off, stepped into the shower, pulled the curtain shut and squeezed the trigger.

Two weeks later, Johnson and his wife joined the Survivors of Suicide group. Three years later, they became facilitators to help others process their grief.

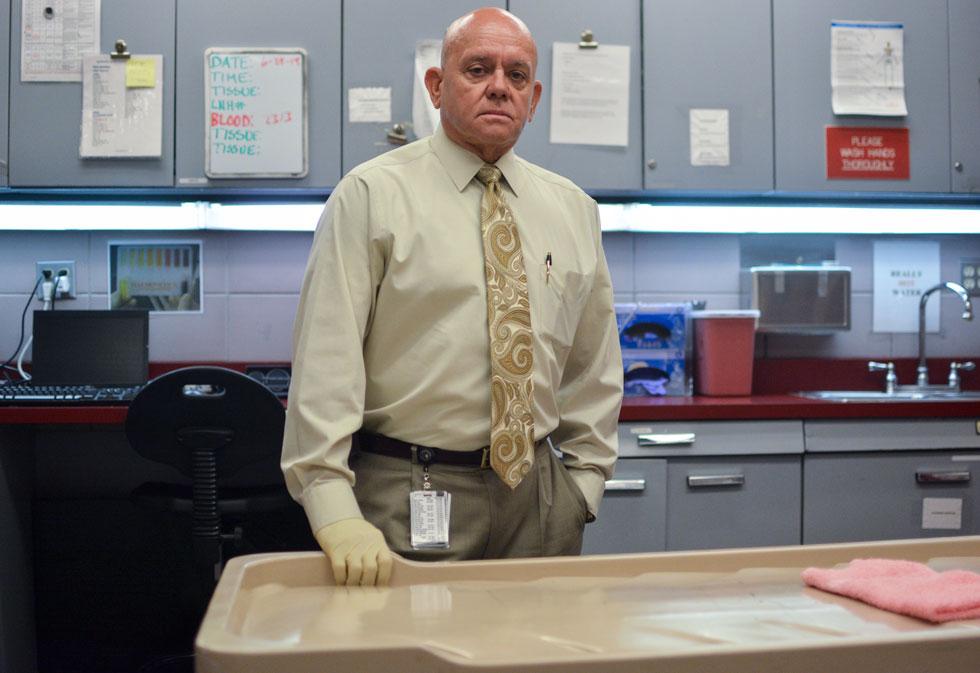

Clark County coroner Michael Murphy spends time helping Las Vegas-area families cope after they lose a loved one to suicide. He can’t provide much solace because he can only tell a family how their loved one committed suicide, but not why — the burning question for most.

“They do not bring a child into this world with the idea that the child’s death will precede them,” Murphy said. “Everything’s out of order for them at that point. And then when they look at what they consider to be a senseless act that someone has done and done to themselves, it leaves them with this emptiness and I don’t know if there’s anything that will fill that void.”

Clark County Coroner Michael Murphy stands in one of the receiving rooms of his office on July 2, 2014. Photo by Jacob Byk/News21.

Regardless of the means, suicide is a mental health issue to Murphy. The solution is increasing awareness of the problem and treating it as such, he said. It’s difficult to know what prevention practices work best because statistically, it’s hard to measure what hasn’t happened, Murphy said.

State prevention measures

Prevention specialists in New Hampshire and Nevada are looking at firearm suicides and working with gun stores and ranges to decrease deaths.

Nevada had a high rate of suicide by firearm, 9.83 per 100,000 residents, or 268 suicides, in 2012, the News21 analysis found. It was ninth in the 13 states that make up the West — the region that accounts for some of the highest rates as a whole.

More than three times as many firearm suicides as firearm homicides happened in Nevada in 2012, data shows.

The Nevada Office of Suicide Prevention has coordinators contacting gun stores, ranges and training centers with pamphlets and posters about gun safety. They also train employees to recognize suicidal or distressed customers, said Richard Egan, prevention training and outreach facilitator.

Egan took the Office of Suicide Prevention job after a long Air Force career. He regularly staffs the office’s booth at gun shows to talk to people about firearm safety and suicide.

He teaches employees of gun ranges and stores to recognize suicidal tendencies of customers in a three-hour class called safeTalk.

“Suicide breeds isolation and darkness — open the door and turn on the light,” Egan said. “Talk to them about what they’re going through. Let them express their feelings. And it may not always be about suicide, but you’re not going to know until you ask.”

Nevada is expanding on safety programs that started on the East Coast.

New Hampshire had a firearm suicide rate of 7.36 per 100,000 people with 97 suicides in 2012, according to News21 data. That put it at more than double the average rate of Northeastern states and slightly above the national average rate. Firearm suicides were nearly nine times higher than the 11 firearm homicides in 2012.

Within five days of each other in 2009, three individuals walked into Riley’s Sport Shop in Hooksett, New Hampshire, and bought firearms they used to kill themselves hours later. Elaine Frank, creator of the New Hampshire Firearm Safety Coalition — of which the sport shop was a member — worked together with the owner of Riley’s to create the Gun Shop Project.

The project — seeking to start suicide prevention conversations among gun owners and sellers — has distributed materials for suicide prevention to more than half of New Hampshire gun stores.

In 2011, the Gun Shop Project added a commandment addressing suicide to the previously established “10 Commandments of Firearm Safety” created by gun manufacturer Remington. The new commandment says “If a loved one is at risk for suicide, keep firearms away from them.”

Suicide is preventable up to a point, Frank said. But there will always be a few individuals who give no warning and will end their lives by any means available. “There are many people who are suicidally ambivalent. They’re not sure that they want to live, but they’re really not sure they want to die,” Frank said.

Counter employees at The Range 702 in Las Vegas are sent to safeTalk training to learn to identify the warning signs of potentially suicidal customers, gunsmith Bill Smallwood said.

Smallwood hasn’t yet been through the training, but after knowing four people who committed suicide — including his best friend — he feels like he can recognize the signs.

Smallwood was in Washington, D.C., when he got a 1 a.m. call about his best friend’s suicide. He was on the first plane home to Las Vegas to be there for Danny Wortman’s wife and family.

“I didn’t see it coming,” he said.

Wortman came home and went upstairs for a long period of time, Smallwood said. When his wife went to the bedroom to check on him, she found him with a revolver to his head. She screamed “What are you doing?” and tried to pull the gun away.

He pulled the trigger. Click. He put the gun to his head a second time and pulled the trigger. It went off.

“Going through so many (suicides) and going through what I did, I pretty much know what to look for,” Smallwood said.

For gun shop employees who haven’t experienced suicides, it’s important to know how to recognize warning signs, he said. “It’s something everybody in the building watches out for,” he said.

Employees know it’s a red flag when a customer asks to rent a gun but doesn’t care what kind. When they only ask for one or two bullets, employees know to be cautious, Smallwood said.

That’s when a counter employee will call over Smallwood or another manager for a second opinion. If a manager feels uncomfortable giving the person a gun, service will be denied. Smallwood keeps a stack of brochures and phone numbers in his office he can give to people who seem to need help.

After the person leaves, employees of Range 702 will call every other gun range in town and warn them not to rent a gun to the at-risk individual, Smallwood said.

“People move here for the good life and then you get sucked into Sin City,” Smallwood said. “It is Las Vegas. You start at the penny machine, move up to the nickel machine, then you’re off to the quarter machine and then you’re on to the dollar machine, then you’re spending the rent and it just goes up like that.”

Discount Firearms and Ammo, a gun shop and range in Las Vegas, experienced a suicide about five years ago, operations manager Ron Reyes said.

A suicide will happen at any range if it has been open long enough, Reyes said. Ranges see more red flags and have more ability to stop suicidal customers if they are renting guns, as opposed to bringing their own. But gun ranges hire gun safety officers to provide oversight on the range, spot customers acting irregularly and prevent any incidents, he said.

“It’s a sad instance when it happens to anybody and when it’s as close as within our doors,” Reyes said. “The range officers, where that’s their daily work area, every time they pass by that lane they know something that other people don’t.”

Politicians told Linda Flatt, who helped create the Nevada Office of Suicide Prevention and was a former suicide prevention trainer, not to bring up guns or gun safety from the beginning of her crusade for suicide prevention resources in Nevada.

Before the office was created in 2003, Sen. Ann O’Connell, R-Las Vegas, who sponsored legislation Flatt worked on, told her any mention of gun safety or gun control paired with suicide prevention talk would kill any progress for help to curb suicides.

Linda Flatt's son, Paul Tillander, killed himself in 1993. After his death, Flatt helped found the Nevada Suicide Prevention Office at the state Division of Public and Behavioral Health. She partners with gun stores, ranges and shows to make gun owners more aware of firearm suicide. Photo by Jacob Byk/News21.

Now, Flatt is amazed the office and its director, Richard Egan, are addressing it.

After her 25-year-old son, Paul Tillander, committed suicide in 1993, Flatt was adamant in thinking suicides were unpreventable. More than a decade later, she’s convinced the creation of the Office of Suicide Prevention and its work have helped decrease the high rate of suicide in the state.

Nevada had the highest rate of suicides and firearm suicides among all states in 1999, and was still in the top five for both in 2003 before the office was created, according to data gathered from the CDC. Flatt attributed high suicide rates to high gun ownership in the state and large rural areas with feelings of isolation and a go-it-alone mentality among residents.

By 2012, Nevada ranked 15th for firearm suicides, the News21 analysis shows. Flatt believes her work and that of her colleagues in her former office is the main cause of the drop over the years.

“I decided I was not going to be destroyed by this,” Flatt said of her son’s suicide. “There was only going to be one death, and that was his.”