In California, shootings offer contrast with perception of state's model laws

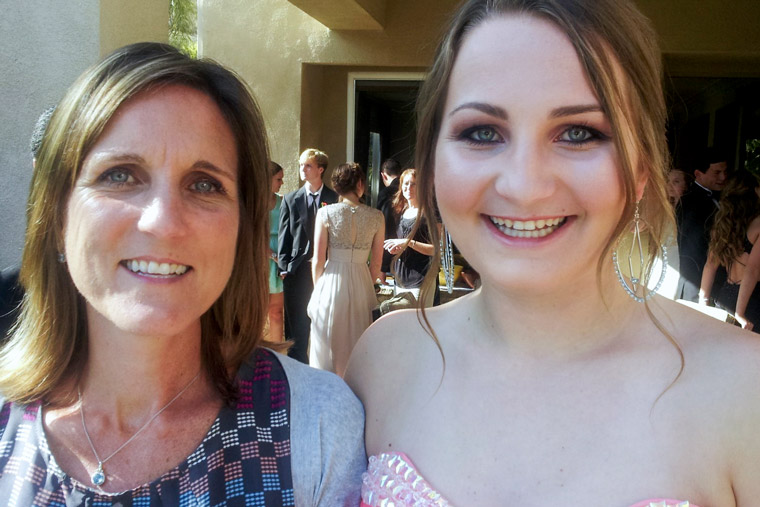

Amanda Wilcox’s hallway walls are lined with photos of her three children — Laura, Caleb and Nathan — in dated wooden frames. The children in the photos are elementary school-aged.

Amanda intended to update the photos as her children grew up, but she never got around to it. Caleb, 30, is now a pilot and Nathan, 27, works in the financial services industry. But Laura, the Wilcoxes’ oldest child and only daughter, was shot and killed on Jan. 10, 2001.

Laura was home for winter break during her sophomore year at Haverford College. She was working as a receptionist at the Nevada County mental health clinic near her parents’ home when she was killed. Scott Thorpe, a clinic patient, shot Laura four times through the window with a 9 mm pistol. When police found Laura’s body, she was still holding her pen.

Gun control advocates tout California as the model state for gun laws. In 2013, the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence gave California an A- based on the strength of its gun-control laws. Thirty-three states received a D+ or lower.

Current and former students of University of California at Santa Barbara try to move on after this summer’s shooting in Isla Vista.

But recent shootings like the one near Santa Barbara — in which four people died by gunfire, including the shooter, and another three people were stabbed to death — have once again incited debate on gun laws. Gun control advocates maintain that more laws need to be enacted, especially laws limiting access to guns for people with mental health problems.

Gun rights advocates contend that gun control laws infringe on law-abiding citizens’ rights and will not prevent determined criminals from committing crimes. In fact, some gun rights groups say their membership is growing in California, as is support for their cause.

Amanda and her husband, Nick, never thought violence would touch their lives. They built their spacious house on 29 acres of remote woodland in the Sierra Nevada foothills two hours north of Sacramento. Nick was an environmental scientist for the state of California and Amanda was a stay-at-home mom. They thought they had found the perfect place to raise a family. But then the Wilcoxes got the call that their 19-year-old daughter had been killed in a rampage shooting.

“Life turned upside down,” Amanda Wilcox said. “I was in shock for six months. Every single aspect of our life changed when we found out Laura was killed. And we lost the future we thought we would have with our daughter.”

Subtle reminders of Laura are scattered throughout the Wilcoxes’ home. Her bed is neatly made with a red-and-white bedspread. A porcelain ballet slipper hangs on her bedroom wall next to a watercolor of a graceful ballerina. Hanging by the door is a beaded keychain that reads “Laura.”

Ask Amanda about Laura, and she begins, without hesitation.

“Laura is 19 years old…”

Amanda and Nick now work as volunteer lobbyists for the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence. After Laura’s death, they found meaning in striving to reform California’s mental health and gun laws. They have been involved in enacting 36 gun control laws in California in the 13 years since Laura’s death, most notably AB 809, which requires the California Department of Justice to retain sales records for long guns, as it already does for handguns. For them the fight is about preventing shooting tragedies from affecting other families.

Landmark legislation

After the Sandy Hook school shooting, the California legislature in 2013 enacted 17 gun-related measures, most tightening firearms restrictions. Gov. Jerry Brown signed laws banning conversion kits for ammunition magazines, strengthening child access prevention requirements and toughening mental health reporting requirements. In late July, Brown signed two more bills: One closed a loophole that allowed single-shot handguns to bypass safety requirements; the other sped up the process of reporting mental health data.

But the victory for gun control advocates has been bittersweet. Brown vetoed seven additional gun control bills in 2013, including a long-sought-after ban on semi-automatic rifles with detachable magazines. In a statement after the veto, Brown said he did not sign the legislation because it included low-capacity rifles commonly used in hunting and target practice. “I don’t believe this bill’s blanket ban on semi-automatic rifles would reduce criminal activity or enhance public safety enough to warrant this infringement on gun owners’ rights,” Brown said in the statement.

“He’s willing to take incremental steps to increase gun safety, but he’s not willing to do something more comprehensive,” said Cody Jacobs, a staff attorney at the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. “I think he believes in an individual’s Second Amendment right and I think he believes gun ownership is or can be at least a positive thing. And he doesn’t want to discourage it.”

Gun control activists like Jacobs look to California as a “first in the nation” state. California was the first state to ban assault weapons and the first to require that all handguns sold in the state pass a safety test to be listed on a roster of guns approved for sale. California is also the only state to ban .50-caliber rifles and require microstamping, a new technology that imprints a serial number on a bullet casing, linking it to information about who purchased the firearm.

“There’s all kinds of examples like that where California’s willing to be the first to do something, and that leads to other states following suit,” said Laura Cutilletta, senior staff attorney for the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence.

Laura Cutilletta

But gun rights activists maintain that new laws don’t solve crime and instead strip away the rights of lawful citizens.

“Really it’s not about the firearms. It’s more of a socioeconomic problem than it is firearms,” said Jake McGuigan, director of state affairs for the National Shooting Sports Foundation. “The only people that are sitting around trying to figure out, ‘Can I own this firearm? Is this legal for me to own? Can I have this? Do I need to register, do this, do that,’ and reading the laws are the people you don’t really need to be concerned with.”

And while gun control activists in California believe they have reached a middle ground, many gun rights activists believe the middle ground has already been lost.

“It’s challenging because I fully understand the desire to protect the citizenry, but it is equally as important to protect the rights of the citizenry,” said Craig DeLuz, spokesman for the California Association of Federal Firearms Licensees (CAL-FFL) and the CalGuns Foundation.